Some Poems

Biography

Images

Videos

Books

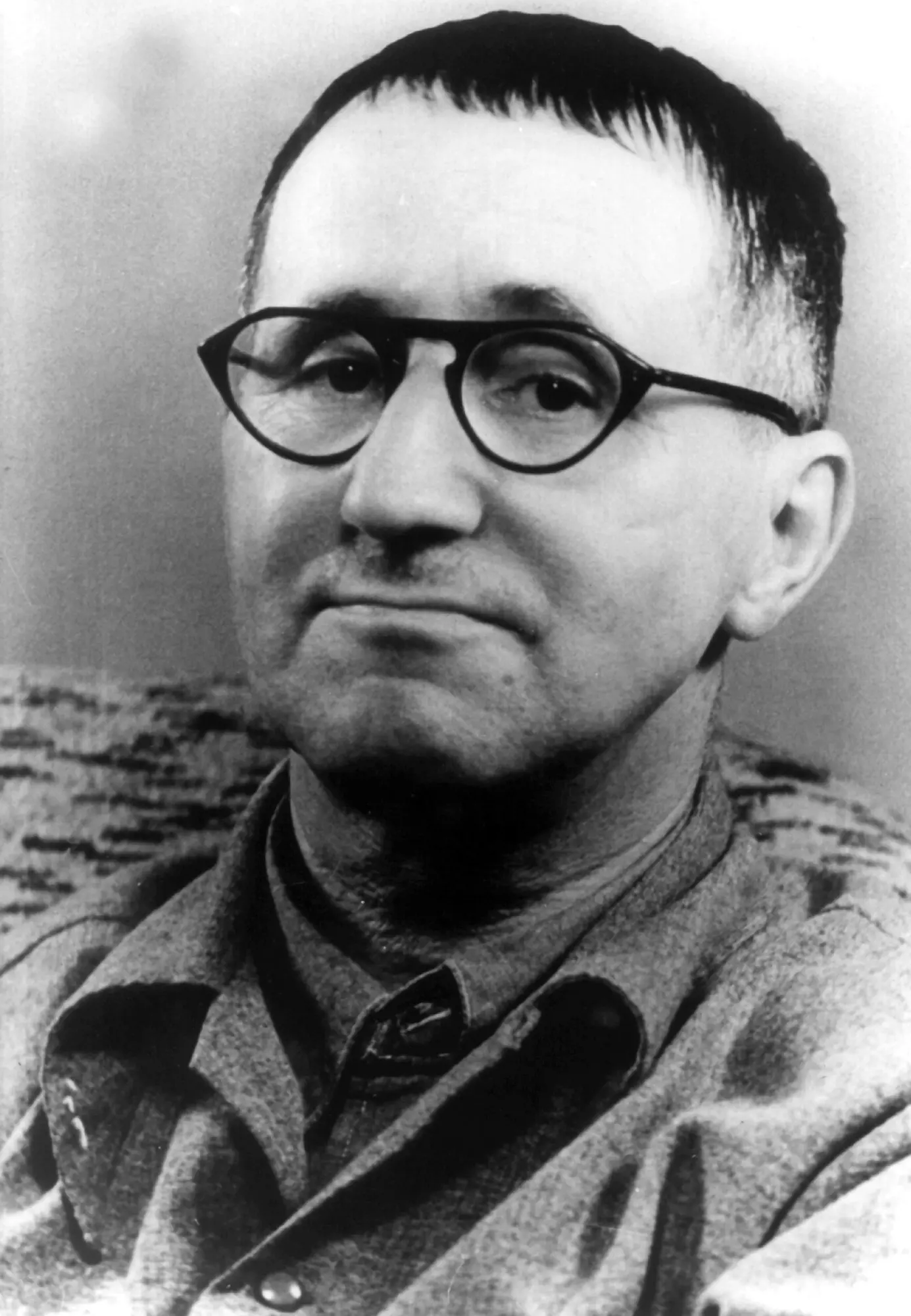

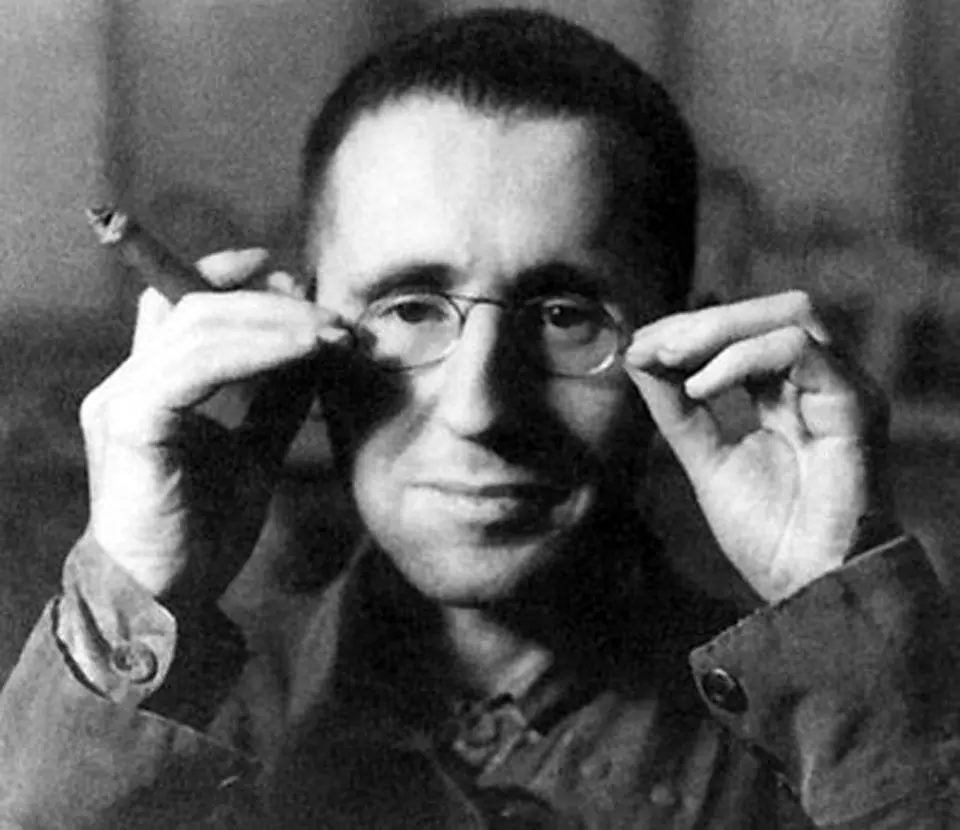

Bertolt Brecht (10 February 1898 – 14 August 1956)

Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht; was a German poet, playwright, and theatre

director.

An influential theatre practitioner of the 20th century, Brecht made equally

significant contributions to dramaturgy and theatrical production, the latter

particularly through the seismic impact of the tours undertaken by the

Berliner Ensemble — the post-war theatre company operated by Brecht and

his wife, long-time collaborator and actress Helene Weigel.

Life and Career

Bavaria (1898–1924)

Bertolt Brecht was born in Augsburg, Bavaria, (about 50 miles (80 km)

north-west of Munich) to a conventionally-devout Protestant mother and a

Catholic father (who had been persuaded to have a Protestant wedding). His

father worked for a paper mill, becoming its managing director in 1914.

Thanks to his mother's influence, Brecht knew the Bible, a familiarity that

would impact on his writing throughout his life. From her, too, came the

"dangerous image of the self-denying woman" that recurs in his drama.

Brecht's home life was comfortably middle class, despite what his occasional

attempt to claim peasant origins implied. At school in Augsburg he met

Caspar Neher, with whom he formed a lifelong creative partnership, Neher

designing many of the sets for Brecht's dramas and helping to forge the

distinctive visual iconography of their epic theatre.

When he was 16, the First World War broke out. Initially enthusiastic, Brecht

soon changed his mind on seeing his classmates "swallowed by the army".

On his father's recommendation, Brecht sought a loophole by registering for

an additional medical course at Munich University, where he enrolled in

1917. There he studied drama with Arthur Kutscher, who inspired in the

young Brecht an admiration for the iconoclastic dramatist and cabaret-star

Wedekind.

From July 1916, Brecht's newspaper articles began appearing under the new

name "Bert Brecht" (his first theatre criticism for the Augsburger Volkswille

appeared in October 1919). Brecht was drafted into military service in the

autumn of 1918, only to be posted back to Augsburg as a medical orderly in

a military VD clinic; the war ended a month later.

In July 1919, Brecht and Paula Banholzer (who had begun a relationship in

1917) had a son, Frank. In 1920 Brecht's mother died.

Some time in either 1920 or 1921, Brecht took a small part in the political

cabaret of the Munich comedian Karl Valentin. Brecht's diaries for the next

few years record numerous visits to see Valentin perform. Brecht compared

Valentin to Chaplin, for his "virtually complete rejection of mimicry and cheap

psychology". Writing in his Messingkauf Dialogues years later, Brecht

identified Valentin, along with Wedekind and Büchner, as his "chief

influences" at that time:

But the man he [Brecht writes of himself in the third person] learnt most

from was the clown Valentin, who performed in a beer-hall. He did short

sketches in which he played refractory employees, orchestral musicians or

photographers, who hated their employers and made them look ridiculous.

The employer was played by his partner, a popular woman comedian who

used to pad herself out and speak in a deep bass voice.

Brecht's first full-length play, Baal (written 1918), arose in response to an

argument in one of Kutscher's drama seminars, initiating a trend that

persisted throughout his career of creative activity that was generated by a

desire to counter another work (both others' and his own, as his many

adaptations and re-writes attest). "Anyone can be creative," he quipped, "it's

rewriting other people that's a challenge." Brecht completed his second

major play, Drums in the Night, in February 1919.

In 1922 while still living in Munich, Brecht came to the attention of an

influential Berlin critic, Herbert Ihering: "At 24 the writer Bert Brecht has

changed Germany's literary complexion overnight"—he enthused in his

review of Brecht's first play to be produced, Drums in the Night—"[he] has

given our time a new tone, a new melody, a new vision. [...] It is a language

you can feel on your tongue, in your gums, your ear, your spinal column." In

November it was announced that Brecht had been awarded the prestigious

Kleist Prize (intended for unestablished writers and probably Germany's most

significant literary award, until it was abolished in 1932) for his first three

plays (Baal, Drums in the Night, and In the Jungle, although at that point

only Drums had been produced). The citation for the award insisted that:

"[Brecht's] language is vivid without being deliberately poetic, symbolical

without being over literary. Brecht is a dramatist because his language is felt

physically and in the round."

That year he married the Viennese opera-singer Marianne Zoff. Their

daughter—Hanne Hiob (1923–2009)—was a successful German actress.

In 1923, Brecht wrote a scenario for what was to become a short slapstick

film, Mysteries of a Barbershop, directed by Erich Engel and starring Karl

Valentin. Despite a lack of success at the time, its experimental

inventiveness and the subsequent success of many of its contributors have

meant that it is now considered one of the most important films in German

film history. In May of that year, Brecht's In the Jungle premiered in Munich,

also directed by Engel. Opening night proved to be a "scandal"—a

phenomenon that would characterize many of his later productions during

the Weimar Republic—in which Nazis blew whistles and threw stink bombs at

the actors on the stage.

In 1924 Brecht worked with the novelist and playwright Lion Feuchtwanger

(whom he had met in 1919) on an adaptation of Christopher Marlowe's

Edward II that proved to be a milestone in Brecht's early theatrical and

dramaturgical development. Brecht's Edward II constituted his first attempt

at collaborative writing and was the first of many classic texts he was to

adapt. As his first solo directorial début, he later credited it as the germ of

his conception of "epic theatre". That September, a job as assistant

dramaturg at Max Reinhardt's Deutsches Theater—at the time one of the

leading three or four theatres in the world—brought him to Berlin.

Weimar Republic Berlin (1925–33)

In 1923 Brecht's marriage to Zoff began to break down (though they did not

divorce until 1927). Brecht had become involved with both Elisabeth

Hauptmann and Helene Weigel. Brecht and Weigel's son, Stefan, was born in

October 1924.

In his role as dramaturg, Brecht had much to stimulate him but little work of

his own. Reinhardt staged Shaw's Saint Joan, Goldoni's Servant of Two

Masters (with the improvisational approach of the commedia dell'arte in

which the actors chatted with the prompter about their roles), and

Pirandello's Six Characters in Search of an Author in his group of Berlin

theatres. A new version of Brecht's third play, now entitled Jungle: Decline of

a Family, opened at the Deutsches Theater in October 1924, but was not a

success.

At this time Brecht revised his important "transitional poem", "Of Poor BB".

In 1925, his publishers provided him with Elisabeth Hauptmann as an

assistant for the completion of his collection of poems, Devotions for the

Home (Hauspostille, eventually published in January 1927). She continued to

work with him after the publisher's commission ran out.

In 1925 in Mannheim the artistic exhibition Neue Sachlichkeit ("new

objectivity") had given its name to the new post-Expressionist movement in

the German arts. With little to do at the Deutsches Theater, Brecht began to

develop his Man Equals Man project, which was to become the first product

of "the 'Brecht collective'—that shifting group of friends and collaborators on

whom he henceforward depended." This collaborative approach to artistic

production, together with aspects of Brecht's writing and style of theatrical

production, mark Brecht's work from this period as part of the Neue

Sachlichkeit movement. The collective's work "mirrored the artistic climate of

the middle 1920s," Willett and Manheim argue:

with their attitude of 'Neue Sachlichkeit' (or New Matter-of-Factness), their

stressing of the collectivity and downplaying of the individual, and their new

cult of Anglo-Saxon imagery and sport. Together the "collective" would go to

fights, not only absorbing their terminology and ethos (which permeates Man

Equals Man) but also drawing those conclusions for the theatre as a whole

which Brecht set down in his theoretical essay "Emphasis on Sport" and tried

to realise by means of the harsh lighting, the boxing-ring stage and other

anti-illusionistic devices that henceforward appeared in his own productions.

In 1925, Brecht also saw two films that had a significant influence on him:

Chaplin's The Gold Rush and Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin. Brecht had

compared Valentin to Chaplin, and the two of them provided models for Galy

Gay in Man Equals Man. Brecht later wrote that Chaplin "would in many ways

come closer to the epic than to the dramatic theatre's requirements." They

met several times during Brecht's time in the United States, and discussed

Chaplin's Monsieur Verdoux project, which it is possible Brecht influenced.

In 1926 a series of short stories was published under Brecht's name, though

Hauptmann was closely associated with writing them. Following the

production of Man Equals Man in Darmstadt that year, Brecht began studying

Marxism and socialism in earnest, under the supervision of Hauptmann.

"When I read Marx's Capital", a note by Brecht reveals, "I understood my

plays." Marx was, it continues, "the only spectator for my plays I'd ever

come across."

In 1927 Brecht became part of the "dramaturgical collective" of Erwin

Piscator's first company, which was designed to tackle the problem of finding

new plays for its "epic, political, confrontational, documentary theatre".

Brecht collaborated with Piscator during the period of the latter's landmark

productions, Hoppla, We're Alive! by Toller, Rasputin, The Adventures of the

Good Soldier Schweik, and Konjunktur by Lania. Brecht's most significant

contribution was to the adaptation of the unfinished episodic comic novel

Schweik, which he later described as a "montage from the novel". The

Piscator productions influenced Brecht's ideas about staging and design, and

alerted him to the radical potentials offered to the "epic" playwright by the

development of stage technology (particularly projections). What Brecht took

from Piscator "is fairly plain, and he acknowledged it" Willett suggests:

The emphasis on Reason and didacticism, the sense that the new subject

matter demanded a new dramatic form, the use of songs to interrupt and

comment: all these are found in his notes and essays of the 1920s, and he

bolstered them by citing such Piscatorial examples as the step-by-step

narrative technique of Schweik and the oil interests handled in Konjunktur

('Petroleum resists the five-act form').

Brecht was struggling at the time with the question of how to dramatize the

complex economic relationships of modern capitalism in his unfinished

project Joe P. Fleischhacker (which Piscator's theatre announced in its

programme for the 1927–28 season). It wasn't until his Saint Joan of the

Stockyards (written between 1929–1931) that Brecht solved it. In 1928 he

discussed with Piscator plans to stage Shakespeare's Julius Caesar and

Brecht's own Drums in the Night, but the productions did not materialize.

1927 also saw the first collaboration between Brecht and the young

composer Kurt Weill. Together they began to develop Brecht's Mahagonny

project, along thematic lines of the biblical Cities of the Plain but rendered in

terms of the Neue Sachlichkeit's Amerikanismus, which had informed

Brecht's previous work. They produced The Little Mahagonny for a music

festival in July, as what Weill called a "stylistic exercise" in preparation for

the large-scale piece. From that point on Caspar Neher became an integral

part of the collaborative effort, with words, music and visuals conceived in

relation to one another from the start. The model for their mutual articulation

lay in Brecht's newly-formulated principle of the "separation of the

elements", which he first outlined in "The Modern Theatre is the Epic

Theatre" (1930). The principle, a variety of montage, proposed by-passing

the "great struggle for supremacy between words, music and production" as

Brecht put it, by showing each as self-contained, independent works of art

that adopt attitudes towards one another.

In 1930 Brecht married Weigel; their daughter Barbara Brecht was born soon

after the wedding. She also became an actress and currently holds the

copyrights to all of Brecht's work.

Brecht formed a writing collective which became prolific and very influential.

Elisabeth Hauptmann, Margarete Steffin, Emil Burri, Ruth Berlau and others

worked with Brecht and produced the multiple teaching plays, which

attempted to create a new dramaturgy for participants rather than passive

audiences. These addressed themselves to the massive worker arts

organisation that existed in Germany and Austria in the 1920s. So did

Brecht's first great play, Saint Joan of the Stockyards, which attempted to

portray the drama in financial transactions.

This collective adapted John Gay's The Beggar's Opera, with Brecht's lyrics

set to music by Kurt Weill. Retitled The Threepenny Opera (Die

Dreigroschenoper) it was the biggest hit in Berlin of the 1920s and a

renewing influence on the musical worldwide. One of its most famous lines

underscored the hypocrisy of conventional morality imposed by the Church,

working in conjunction with the established order, in the face of

working-class hunger and deprivation:

Erst kommt das Fressen

Dann kommt die Moral.

First the grub (lit. "eating like animals, gorging")

Then the morality.

The success of The Threepenny Opera was followed by the quickly thrown

together Happy End. It was a personal and a commercial failure. At the time

the book was purported to be by the mysterious Dorothy Lane (now known

to be Elisabeth Hauptmann, Brecht's secretary and close collaborator).

Brecht only claimed authorship of the song texts. Brecht would later use

elements of Happy End as the germ for his Saint Joan of the Stockyards, a

play that would never see the stage in Brecht's lifetime. Happy End's score

by Weill produced many Brecht/Weill hits like "Der Bilbao-Song" and

"Surabaya-Jonny".

The masterpiece of the Brecht/Weill collaborations, Rise and Fall of the City

of Mahagonny (Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny), caused an uproar

when it premiered in 1930 in Leipzig, with Nazis in the audience protesting.

The Mahagonny opera would premier later in Berlin in 1931 as a triumphant

sensation.

Brecht spent his last years in the Weimar-era Berlin (1930–1933) working

with his "collective" on the Lehrstücke. These were a group of plays driven

by morals, music and Brecht's budding epic theatre. The Lehrstücke often

aimed at educating workers on Socialist issues. The Measures Taken (Die

Massnahme) was scored by Hanns Eisler. In addition, Brecht worked on a

script for a semi-documentary feature film about the human impact of mass

unemployment, Kuhle Wampe (1932), which was directed by Slatan Dudow.

This striking film is notable for its subversive humour, outstanding

cinematography by Günther Krampf, and Hanns Eisler's dynamic musical

contribution. It still provides a vivid insight into Berlin during the last years of

the Weimar Republic. The so-called "Westend Berlin Scene" in the 1930 was

an important influencing factor on Brecht, playing in a milieu around

Ulmenallee in Westend with artists like Richard Strauss, Marlene Dietrich and

Herbert Ihering.

By February 1933, Brecht’s work was eclipsed by the rise of Nazi rule in

Germany. (Brecht would also have his work challenged again in later life by

the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), which believed he

was under the influence of communism.)

Nazi Germany and World War II (1933–1945)

Fearing persecution, Brecht left Germany in February 1933, when Hitler took

power. He went to Denmark, but when war seemed imminent in April 1939,

he moved to Stockholm, Sweden, where he remained for a year. Then Hitler

invaded Norway and Denmark, and Brecht was forced to leave Sweden for

Helsinki in Finland where he waited for his visa for the United States until 3

May 1941.

During the war years, Brecht became a prominent writer of the Exilliteratur.

He expressed his opposition to the National Socialist and Fascist movements

in his most famous plays: Life of Galileo, Mother Courage and Her Children,

The Good Person of Szechwan, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, The

Caucasian Chalk Circle, Fear and Misery of the Third Reich, and many others.

Brecht also wrote the screenplay for the Fritz Lang-directed film Hangmen

Also Die! which was loosely based on the 1942 assassination of Reinhard

Heydrich, the Nazi Reich Protector of German-occupied Prague, number-two

man in the SS, and a chief architect of the Holocaust, who was known as

"The Hangman of Prague." It was Brecht's only script for a Hollywood film:

the money he earned from the project enabled him to write The Visions of

Simone Machard, Schweik in the Second World War and an adaptation of

Webster's The Duchess of Malfi. Hanns Eisler was nominated for an Academy

Award for his musical score. The collaboration of three prominent refugees

from Nazi Germany –Lang, Brecht and Eisler – is an example of the influence

this generation of German exiles had in American culture.

Cold War and final years in East Germany (1945–1956)

In the years of the Cold War and "Red Scare", Brecht was blacklisted by

movie studio bosses and interrogated by the House Un-American Activities

Committee. Along with about 41 other Hollywood writers, directors, actors

and producers, he was subpoenaed to appear before the HUAC in September

1947. Although he was one of 19 witnesses who declared that they would

refuse to appear, Brecht eventually decided to testify. He later explained that

he had followed the advice of attorneys and had not wanted to delay a

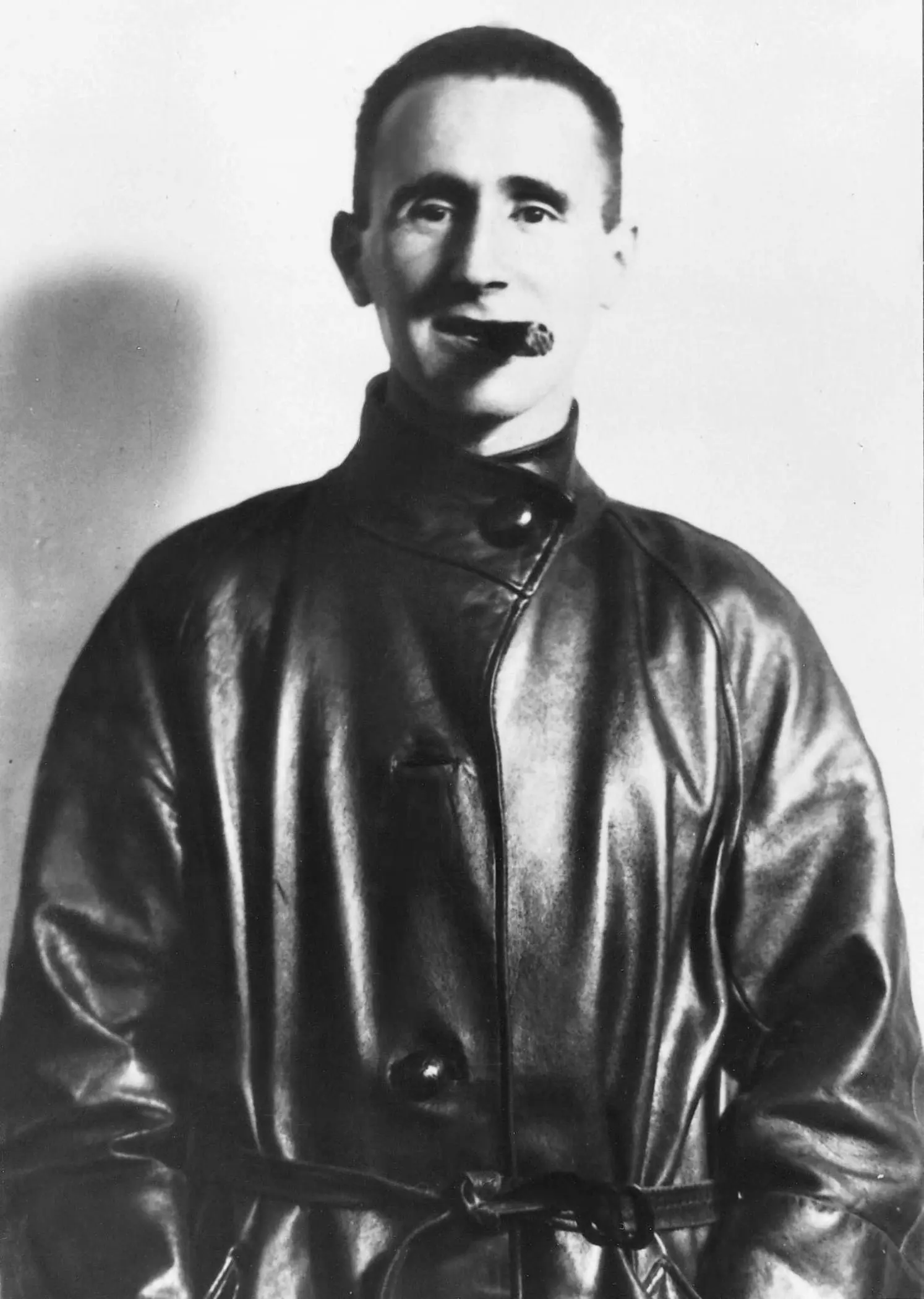

planned trip to Europe. Dressed in overalls and smoking an acrid cigar that

made some of the committee members feel slightly ill, on 30 October 1947

Brecht testified that he had never been a member of the Communist Party.

He made wry jokes throughout the proceedings, punctuating his inability to

speak English well with continuous references to the translators present, who

transformed his German statements into English ones unintelligible to

himself. HUAC Vice Chairman Karl Mundt thanked Brecht for his

co-operation. The remaining witnesses, the so called Hollywood Ten, refused

to testify and were cited for contempt. Brecht's decision to appear before the

committee led to criticism, including accusations of betrayal. The day after

his testimony, on 31 October, Brecht returned to Europe.

In Chur in Switzerland, Brecht staged an adaptation of Sophocles' Antigone,

based on a translation by Hölderlin. It was published under the title

Antigonemodell 1948, accompanied by an essay on the importance of

creating a "non-Aristotelian" form of theatre. An offer of his own theatre

(completed in 1954) and theatre company (the Berliner Ensemble)

encouraged Brecht to return to Berlin in 1949. He retained his Austrian

nationality (granted in 1950) and overseas bank accounts from which he

received valuable hard currency remittances. The copyrights on his writings

were held by a Swiss company. At the time he drove a pre-war DKW car—a

rare luxury in the austere divided capital.

Though he was never a member of the Communist Party, Brecht had been

deeply schooled in Marxism by the dissident communist Karl Korsch. Korsch's

version of the Marxist dialectic influenced Brecht greatly, both his aesthetic

theory and theatrical practice. Brecht received the Stalin Peace Prize in 1954.

Brecht wrote very few plays in his final years in East Berlin, none of them as

famous as his previous works. He dedicated himself to directing plays and

developing the talents of the next generation of young directors and

dramaturgs, such as Manfred Wekwerth, Benno Besson and Carl Weber.

Some of his most famous poems, including the "Buckow Elegies", were

written at this time.

At first Brecht supported the measures taken by the East German

government against the Uprising of 1953 in East Germany, which included

the use of Soviet military force. In a letter from the day of the uprising to

SED First Secretary Walter Ulbricht, Brecht wrote that: "History will pay its

respects to the revolutionary impatience of the Socialist Unity Party of

Germany. The great discussion [exchange] with the masses about the speed

of socialist construction will lead to a viewing and safeguarding of the

socialist achievements. At this moment I must assure you of my allegiance to

the Socialist Unity Party of Germany."

Brecht's subsequent commentary on those events, however, offered a

different assessment—in one of the poems in the Elegies, "Die Lösung" (The

Solution), Brecht writes:

After the uprising of the 17th of June

The Secretary of the Writers Union

Had leaflets distributed in the Stalinallee

Stating that the people

Had forfeited the confidence of the government

And could win it back only

By redoubled efforts. Would it not be easier

In that case for the government

To dissolve the people

And elect another?

Death

Brecht died on 14 August 1956 of a heart attack at the age of 58. He is

buried in the Dorotheenstädtischer cemetery on Chausseestraße in the Mitte

neighbourhood of Berlin, overlooked by the residence he shared with Helene

Weigel.

Theory and Practice of Theatre

From his late twenties Brecht remained a lifelong committed Marxist who, in

developing the combined theory and practice of his "epic theatre",

synthesized and extended the experiments of Erwin Piscator and Vsevolod

Meyerhold to explore the theatre as a forum for political ideas and the

creation of a critical aesthetics of dialectical materialism.

Epic Theatre proposed that a play should not cause the spectator to identify

emotionally with the characters or action before him or her, but should

instead provoke rational self-reflection and a critical view of the action on the

stage. Brecht thought that the experience of a climactic catharsis of emotion

left an audience complacent. Instead, he wanted his audiences to adopt a

critical perspective in order to recognise social injustice and exploitation and

to be moved to go forth from the theatre and effect change in the world

outside. For this purpose, Brecht employed the use of techniques that remind

the spectator that the play is a representation of reality and not reality itself.

By highlighting the constructed nature of the theatrical event, Brecht hoped

to communicate that the audience's reality was equally constructed and, as

such, was changeable.

Brecht's modernist concern with drama-as-a-medium led to his refinement of

the "epic form" of the drama. This dramatic form is related to similar

modernist innovations in other arts, including the strategy of divergent

chapters in James Joyce's novel Ulysses, Sergei Eisenstein's evolution of a

constructivist "montage" in the cinema, and Picasso's introduction of cubist

"collage" in the visual arts.

One of Brecht's most important principles was what he called the

Verfremdungseffekt (translated as "defamiliarization effect", "distancing

effect", or "estrangement effect", and often mistranslated as "alienation

effect"). This involved, Brecht wrote, "stripping the event of its self-evident,

familiar, obvious quality and creating a sense of astonishment and curiosity

about them". To this end, Brecht employed techniques such as the actor's

direct address to the audience, harsh and bright stage lighting, the use of

songs to interrupt the action, explanatory placards, and, in rehearsals, the

transposition of text to the third person or past tense, and speaking the

stage directions out loud.

In contrast to many other avant-garde approaches, however, Brecht had no

desire to destroy art as an institution; rather, he hoped to "re-function" the

theatre to a new social use. In this regard he was a vital participant in the

aesthetic debates of his era—particularly over the "high art/popular culture"

dichotomy—vying with the likes of Adorno, Lukács, Ernst Bloch, and

developing a close friendship with Benjamin. Brechtian theatre articulated

popular themes and forms with avant-garde formal experimentation to

create a modernist realism that stood in sharp contrast both to its

psychological and socialist varieties. "Brecht's work is the most important

and original in European drama since Ibsen and Strindberg," Raymond

Williams argues, while Peter Bürger dubs him "the most important materialist

writer of our time."

Brecht was also influenced by Chinese theatre, and used its aesthetic as an

argument for Verfremdungseffekt. Brecht believed, "Traditional Chinese

acting also knows the alienation effect, and applies it most subtly. ... The

[Chinese] performer portrays incidents of utmost passion, but without his

delivery becoming heated." Brecht attended a Chinese opera performance

and was introduced to the famous Chinese opera performer Mei LanFang in

1935. However, Brecht was sure to distinguish between Epic and Chinese

theatre. He recognized that the Chinese style was not a "transportable piece

of technique," and that Epic theatre sought to historicize and address social

and political issues.

Impact

Brecht left the Berliner Ensemble to his wife, the actress Helene Weigel,

which she ran until her death in 1971. Perhaps the most famous German

touring theatre of the postwar era, it was primarily devoted to performing

Brecht's plays. His son, Stefan Brecht, became a poet and theatre critic

interested in New York's avant-garde theatre. Brecht has been a

controversial figure in Germany, and in his native city of Augsburg there

were objections to creating a birthplace museum. By the 1970s, however,

Brecht's plays had surpassed Shakespeare's in the number of annual

performances in Germany.

There are few areas of modern theatrical culture that have not felt the

impact or influence of Brecht's ideas and practices; dramatists and directors

in whom one may trace a clear Brechtian legacy include: Dario Fo, Augusto

Boal, Joan Littlewood, Peter Brook, Peter Weiss, Heiner Müller, Pina Bausch,

Tony Kushner, Robert Bolt and Caryl Churchill.

In addition to the theatre, Brechtian theories and techniques have exerted

considerable sway over certain strands of film theory and cinematic practice;

Brecht's influence may be detected in the films of Jean-Luc Godard, Lindsay

Anderson, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Joseph Losey, Nagisa Oshima, Ritwik

Ghatak, Lars von Trier, Jan Bucquoy and Hal Hartley.

Brecht in Fiction

In the 1930 novel Success, Brecht's mentor Lion Feuchtwanger immortalized

Brecht as the character Kaspar Pröckl.

In the 2006 film The Lives of Others, a Stasi agent is partially inspired to

save a playwright he has been spying on by reading a book of Brecht poetry

that he had stolen from the artist's apartment.

Brecht at Night by Mati Unt, transl. Eric Dickens (Dalkey Archive Press, 2009)

Collaborators and Associates

Collective and collaborative working methods were inherent to Brecht's

approach, as Fredric Jameson (among others) stresses. Jameson describes

the creator of the work not as Brecht the individual, but rather as 'Brecht': a

collective subject that "certainly seemed to have a distinctive style (the one

we now call 'Brechtian') but was no longer personal in the bourgeois or

individualistic sense." During the course of his career, Brecht sustained many

long-lasting creative relationships with other writers, composers,

scenographers, directors, dramaturgs and actors; the list includes: Elisabeth

Hauptmann, Margarete Steffin, Ruth Berlau, Slatan Dudow, Kurt Weill, Hanns

Eisler, Paul Dessau, Caspar Neher, Teo Otto, Karl von Appen, Ernst Busch,

Lotte Lenya, Peter Lorre, Therese Giehse, Angelika Hurwicz, Carola Neher

and Helene Weigel herself. This is "theatre as collective experiment [...] as

something radically different from theatre as expression or as experience."

Eserleri:

Dramatic Works

Entries show: English-language translation of title (German-language title)

[year written] / [year first produced]

Baal 1918/1923

Drums in the Night (Trommeln in der Nacht) 1918–20/1922

The Beggar (Der Bettler oder Der tote Hund) 1919/?

A Respectable Wedding (Die Kleinbürgerhochzeit) 1919/1926

Driving Out a Devil (Er treibt einen Teufel aus) 1919/?

Lux in Tenebris 1919/?

The Catch (Der Fischzug) 1919?/?

Mysteries of a Barbershop (Mysterien eines Friseursalons) (screenplay) 1923

In the Jungle of Cities (Im Dickicht der Städte) 1921–24/1923

The Life of Edward II of England (Leben Eduards des Zweiten von England)

1924/1924

Downfall of the Egotist Johann Fatzer (Der Untergang des Egoisten Johnann

Fatzer) (fragments) 1926–30/1974

Man Equals Man (Mann ist Mann) 1924–26/1926

The Elephant Calf (Das Elefantenkalb) 1924–26/1926

Little Mahagonny (Mahagonny-Songspiel) 1927/1927

The Threepenny Opera (Die Dreigroschenoper) 1928/1928

The Flight across the Ocean (Der Ozeanflug); originally Lindbergh's Flight

(Lindberghflug) 1928–29/1929

The Baden-Baden Lesson on Consent (Badener Lehrstück vom

Einverständnis) 1929/1929

Happy End (Happy End) 1929/1929

The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt

Mahagonny) 1927–29/1930

He Said Yes / He Said No (Der Jasager; Der Neinsager) 1929–30/1930–?

The Decision (Die Maßnahme) 1930/1930

Saint Joan of the Stockyards (Die heilige Johanna der Schlachthöfe)

1929–31/1959

The Exception and the Rule (Die Ausnahme und die Regel) 1930/1938

The Mother (Die Mutter) 1930–31/1932

Kuhle Wampe (screenplay) 1931/1932

The Seven Deadly Sins (Die sieben Todsünden der Kleinbürger) 1933/1933

Round Heads and Pointed Heads (Die Rundköpfe und die Spitzköpfe)

1931–34/1936

The Horatians and the Curiatians (Die Horatier und die Kuriatier)

1933–34/1958

Fear and Misery of the Third Reich (Furcht und Elend des Dritten Reiches)

1935–38/1938

Señora Carrar's Rifles (Die Gewehre der Frau Carrar) 1937/1937

Life of Galileo (Leben des Galilei) 1937–39/1943

How Much Is Your Iron? (Was kostet das Eisen?) 1939/1939

Dansen (Dansen) 1939/?

Mother Courage and Her Children (Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder) 1938–39/1941

The Trial of Lucullus (Das Verhör des Lukullus) 1938–39/1940

Mr Puntila and his Man Matti (Herr Puntila und sein Knecht Matti) 1940/1948

The Good Person of Szechwan (Der gute Mensch von Sezuan) 1939–42/1943

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui (Der aufhaltsame Aufstieg des Arturo Ui)

1941/1958

Hangmen Also Die! (screenplay) 1942/1943

The Visions of Simone Machard (Die Gesichte der Simone Machard )

1942–43/1957

The Duchess of Malfi 1943/1943

Schweik in the Second World War (Schweyk im Zweiten Weltkrieg)

1941–43/1957

The Caucasian Chalk Circle (Der kaukasische Kreidekreis) 1943–45/1948

Antigone (Die Antigone des Sophokles) 1947/1948

The Days of the Commune (Die Tage der Commune) 1948–49/1956

The Tutor (Der Hofmeister) 1950/1950

The Condemnation of Lucullus (Die Verurteilung des Lukullus) 1938–39/1951

Report from Herrnburg (Herrnburger Bericht) 1951/1951

Coriolanus (Coriolan) 1951–53/1962

The Trial of Joan of Arc of Proven, 1431 (Der Prozess der Jeanne D'Arc zu

Rouen, 1431) 1952/1952

Turandot (Turandot oder Der Kongreß der Weißwäscher) 1953–54/1969

Don Juan (Don Juan) 1952/1954

Trumpets and Drums (Pauken und Trompeten) 1955/1955

Non-dramatic Works

Stories of Mr. Keuner (Geschichten vom Herrn Keuner)

Theoretical Works

"The Modern Theatre is the Epic Theatre" (1930)

"The Threepenny Lawsuit" ("Der Dreigroschenprozess") (written 1931;

published 1932)

"The Book of Changes" (fragment also known as Me-Ti; written 1935–1939)

"The Street Scene" (written 1938; published 1950)

"The Popular and the Realistic" (written 1938; published 1958)

"Short Description of a New Technique of Acting which Produces an

Alienation Effect" (written 1940; published 1951)

"A Short Organum for the Theatre" ("Kleines Organon für das Theater", written 1948; published 1949)

The Messingkauf Dialogues (Dialogue aus dem Messingkauf, published 1963)

BRECHT Introduction

Bertolt Brecht and Epic Theater: Crash Course Theater #44

Quem foi BERTOLT BRECHT I 50 FATOS

Bertolt Brecht & Kurt Weill - Alabama Song

Bertolt Brecht - İyi adama bir iki soru

Kurt Weill & Bertolt Brecht - Pirate Jenny (Sung by Lotte Lenya)

An introduction to Brechtian theatre

Five Truths: Bertolt Brecht

Sub and like Brecht videos otw soon🤞🏾 #clip #callofduty #firstpersonshooter

Quem foi Bertolt Brecht?

Como este homem transformou a humanidade?

Bertolt Brecht - Works and Key Concepts

Bertolt Brecht - Alles was Brecht ist (Portrait, 3sat 1997)

Bertolt Brecht - O ANALFABETO POLÍTICO (Gestus)

Brecht MOTHER COURAGE Berliner Ensemble 1957 ENGLISH SUBTITLES Weigel Busch Hurwicz Schall Kaiser

Bertolt Brecht speaks in the House Committee on Un-American Activities

Kurt Weill / Bertolt Brecht / Lotte Lenya - Die Dreigroschenoper

"Se os tubarões fossem homens" - Bertolt Brecht

Nada É Impossível De Mudar | Poema de Bertolt Brecht com narração de Mundo Dos Poemas

If Sharks Were Men by Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht - Tahterevalli

Die Moritat von Mackie Messer (Die Dreigroschenoper), Kurt Weill - Bertolt Brecht (Lotte Lenya)

Uma aula sobre Bertolt Brecht

Hanns Eisler/Bertolt Brecht - United Front Song (Das Einheitsfrontlied)

Brecht e o teatro épico

Stanford Director Recalls Working with Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht sings (with translation) 'The song of the futility of all human endeavour' (1929)

Bertolt Brecht - Okumuş bir işçi soruyor

Brecht and Epic Theatre.

Bertolt Brecht - The Life Of Galileo (March 5, 1995)

Threepenny Opera, by Kurt Weill (Music) and Bertholt Brecht (Words)

Hanns Eisler/ Bertolt Brecht - Das Einheitsfrontlied/ Το τραγούδι της ενότητας (German/Greek lyrics)

Epic Theatre | Bertolt Brecht || Verfremdungseffekt/Alienation/Estrangement Effect-Writers and Works

David Bowie in Bertolt Brecht's BAAL

Bertolt Brecht - Das Lied von der Unzulänglichkeit des menschlichen Strebens

Solo Performance: Bertolt Brecht - Alienation (1860 Performance)

Bertol Brecht - 'Mack the Knife'

Documental sobre BERTOLT BRECHT

GELECEK KUŞAKLARA/ Bertolt Brecht/Genco Erkal

Ato Criativo | Denise Fraga e o teatro de Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht - Sınıfının İnsanları

QUANDO ME FIZERAM DEIXAR O PAíS - Bertolt Brecht

LAS MEJORES FRASES DE BERTOLT BRECHT

Bertolt Brecht - AOS QUE VIRÃO DEPOIS DE NÓS (Gestus)

"A Worker Reads History," by Bertolt Brecht

Genco Erkal & Tülay Günal - Ben Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht - Yurttaşlarıma

LA BONNE AME DU SE-TCHOUAN de Bertolt BRECHT ( 141 minutes)

Who is Bertolt Brecht ?

Mackie Messer (Mack the Knife) by Kurt Weill & Bertolt Brecht

Escritas.org

Escritas.org